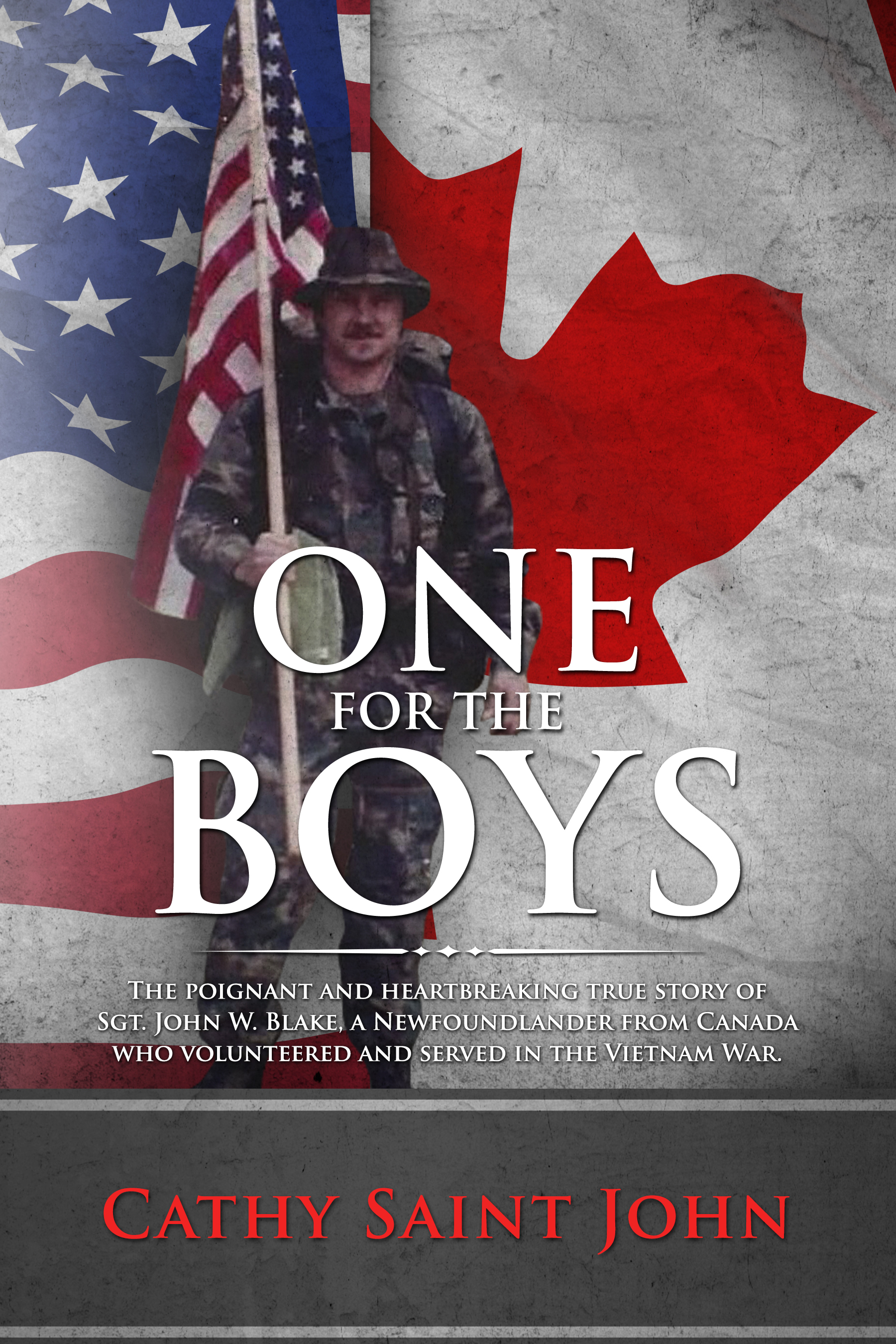

How a Canadian Vietnam veteran from Newfoundland sacrificed all in order to win greater respect for his brothers in arms.

Writing about my late brother and his historical story was not an easy task. It took a tremendous amount of time, sadness, tears, and courage to cross over into John W. Blake’s life struggles and triumphs then finally make the decision to share all with the reader. I could have missed the emotional pain but then I would have missed never knowing a man that no one should ever forget.

The largest compliment I can give to my late brother was to have written his story and gotten it right. It has taken two decades of writing, research, interviews and editing to succeed. The reasoning rests in John’s story, One for the Boys.

My family and I recognized that it was necessary to share John’s story with the public, largely due to the continuous struggle that modern veterans, first responders, civilians, and their families endure. Communities and governments in North America, especially in Canada are mostly inexperienced and unprepared to live with the many facets of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

The heartbreaking day-to-day battle in understanding persons who live with PTSD was compounded by the lack of timeliness in discovery of the illness and the delivery of supports. Plus the intentional and unintentional stigma attached to mental health issues is an ongoing concern. Most importantly, John’s story will offer some clarification as to why too many military personnel and civilians continue to die by their own hand as a result of their injuries pertaining to PTSD.

Our family originated in Topsail, Newfoundland. In retrospect, growing up in Topsail was unique with a lush forest that lends itself daily for games of Cowboys and Indians with a crowd of equally imaginative boys and girls. In 1966, when Newfoundlanders were coming home during the ‘Come Home Year’ festivities, our family was preparing to leave. Ultimately, we settled in Montreal.

I’ll never forget that day in Montreal when my only brothers, John, then nineteen, and David, then seventeen, said they were going to enlist in the United States Army to fight Communism. Canada was not at war with Vietnam, but it did support the United States and South Vietnam by providing military supplies, materials, and so on. Both John and David believed deeply in the need to stop the growing Communist threat in Asia.

Their decision to enlist would change our little family forever. Our mother retreated into a depression for three days before finally surfacing from her bedroom. During that time, we all felt a cloud of sadness hovering over our little home. But it was tempered with pride, because our boys were about to do just as our deceased father, a Great War veteran, had done — journey to a faraway land to fight in a war that was intended to free the oppressed.

David trained and served as a mechanic, working on helicopters in Vietnam, but John — he was a warrior. He spent his time in the war zone, doing extremely dangerous work that brought him in direct contact with the enemy and the many atrocities of war. John lost far too many good friends in Vietnam. A gifted writer, he used his poetry and journals to memorialize the lives of his fellow soldiers. Thoughts of those brave men followed John every day of his life.

It is with hope and a prayer that our brother’s story will make a difference in other families’ lives and assist communities in understanding PTSD. Accepting and respecting our veterans and civilians in their newly formed life is critical in survival. Living with PTSD is a life that most people afflicted cannot openly discuss for fear of traumatizing the people they love with their own painful memories and experiences. John’s story, with a few unique historical exceptions, is not so very different from persons who have died due to their injuries pertaining to PTSD. His story offers the reader an understanding and acceptance of those who struggle and live with mental health issues.

When John died in Hilo, Hawaii on February 13, 1996, I became entrusted with my dear brother’s final request to be buried in a military cemetery at home in Newfoundland. I never dreamt a simple request of burial would become a problematic and devastating way of life. John’s cremains could have been buried at Arlington, the most renowned cemetery in North America.

Blake was the first and only Newfoundlander to earn the renowned ‘Green Beret’ of the United States Army Special Forces

Department of Veterans Affairs Canada (DVA) had rejected John’s family and friends his final request and denied them closure to his death. It was inconceivable to the family that an honorably discharged, decorated-for-valor, Vietnam veteran who was a Canadian and the son of a WWI veteran—would be denied burial in a Canadian military cemetery. But it happened and it was a cruel injustice to a Canadian family of a soldier who had honorably served a Canada’s ally.

Fast forward to now, twenty three years later, tears still sting my eyes when I think about how much John had given to this world and how little he’d received in return. And how, his homeland, Canada, had denied him his final request to rest in peace in Newfoundland. During that period, I often reflect on my brother’s youth, a boy of thirteen who suddenly became the man of the house by acclamation after Dad’s death, to a soldier of barely twenty years old who served two tours in Vietnam. Tours of duty in Vietnam that destroyed the brother we knew and understood. He gave endless assistance to countless U.S. Vietnam veterans, men who gave him reason to ‘hang-on’ and keep fighting. He had walked 3,200 miles across the United States for the ‘boys’ and he, himself, was Canadian. He sacrificed spending time with his family in order to protect each loved one from the heartache and madness of his PTSD. Throughout this time, our family knew that John was struggling with his own PTSD. We also knew that John wanted to come home and to grow old on a mountain overlooking the ocean; but he needed to stay in the U.S., where he could access medical intervention for his PTSD. We had lived and loved him from a distance through telephone calls and letters. In the end, John relinquished his life. He had given up so much and expected so little. We sought only to have his final request respected.

In 1996, a request to DVA Canada was initiated to purchase a small burial plot in the only local military cemetery commonly known as the Field of Honour, St. John’s, NL—A gentle enough request, but not a gentle response.

My family and I were sickened that the Canadian Vietnam veterans (CVV’s) were not accepted as veterans in Canada. We fully understood the rejection that was evident during the ‘bad’ years that followed the Vietnam War in America. The very same misguided ignorance that the Vietnam veterans experienced in the 1970’s was now being felt by our family here in Canada, in 1996—twenty-one years after the end of that War. We knew the difference. Canada had indeed been actively involved in Vietnam, and we were not about to go quietly away. Nor would we accept the disgraceful attitude presented by the Canadian Government’s state of amnesia concerning their participation in the American war effort during the Vietnam War era.

The Government of Canada, specifically Department of Veterans Affairs (DVA) Lawrence MacAulay then Secretary of State, Veterans during the 1990’s and who is currently the newly appointed Minister of Veterans Affairs, Canada had blocked the family’s effort to purchase a burial plot in the only military cemetery in St. John’s, NL. His argument was primarily based on non-existing policies and rhetoric that failed miserably to convince the public that DVA was right in their denial of the family’s request to purchase a burial plot. During that same period, DVA Canada continued to make exceptions for several other burials but continued to blatantly deny a Vietnam veteran a soldier’s burial because he was a Vietnam veteran.

In 1997, Lawrence MacAulay stated; “I would diminish their (meaning the soldier of previous and future wars) honour.” The nationwide campaign, Not Without Honour, ensued for the sole issue of burial for John Blake in the local military cemetery commonly known as the Field of Honour in St. John’s, NL. But that was just the tip of the iceberg. It became a fight for all or any Canadians who served in Vietnam under the American flag and who may require a burial plot in a Field of Honour in Canada. The campaign had gained the respect and support of two million Canadians and Americans—veterans and civilians alike during its five year mandate.

Department of Veterans Affairs Canada (DVA) had gone from bad to worse. In 2005, unknown to the public and without constituent discussion, DVA changed its official Fields of Honour list to include Fields of Honour at St. John’s,Newfoundland & Labrador, and Winnipeg, Manitoba as official Fields of Honour in Canada. This change raised the number of official Fields of Honour from four to six national cemeteries despite the fact that there is a Vietnam veteran who had been buried in 1969 in the Field of Honour at Brookside cemetery in Winnipeg, MB. That decision will have devastating repercussions in the future for many Canadian families of numerous Vietnam veterans living in Winnipeg.

My saddest thought of all is that this horrendous occurrence will happen again to other families in Canada when their Canadian fathers, uncles and brothers who served the United States of America in Vietnam for the freedom of the oppressed die and a request for burial in an only existing military cemetery in the provinces of Newfoundland and Winnipeg will be denied because they are Vietnam veterans.

Blake was the first and only Newfoundlander to earn the renowned ‘Green Beret’ of the United States Army Special Forces and served as an elite sky soldier with N/75th Rangers of the 173rd AIRBORNE BRIDGADE (The Herd).

In 1982, in an attempt to heal the strife of American Veterans and the contemptuous divisiveness felt by its citizens prior to the unveiling of the Vietnam Veteran Memorial Wall in Washington, D.C., Blake became the first person to march 3,200 miles across the entire country, in full uniform, while carrying the United States Flag. He did this without an entourage, GPS or any new-age technology. John relied solely on his Ranger skills, ever remembering the motto: Rangers Lead the Way! More unbelievable still, he was a Newfoundlander from Canadian.

Hailed a tour de force, One For the Boys is a riveting true story of Sgt. John W. Blake’s life. Meticulously written are John Blake’s adventures, historical accomplishment, his vividly detailed struggle in living and coping with injuries pertaining to his Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, and ultimately his self-inflicted death in 1996.

This impressive, heartbreaking account will find the reader unable to resist turning page after page. According to his journal from Vietnam, John experienced valor and the horrors of jungle warfare that included the death of his soldier brothers in Vietnam. John was wounded in both his arms and legs on three different occasions by grenade shrapnel. Each time he declined the offer to be ‘written-up’ by a physician/medic for the renowned Purple Heart award. The Rangers understood that there were worse things than seeing your own blood dripping onto your boots. Most Rangers felt that the Purple Heart was more appropriate for the warriors who suffered life-threatening wounds or ultimately died as a result of their injuries.

Cathy Saint John returned and settled in St. John’s, Newfoundland in 1973. She has enjoyed several careers throughout the past decades. Her most fulfilling career prior to retirement had been working with young adults with disabilities in a post-secondary educational environment. Since the discovery of her brother’s N75thRanger Airborne unit in 2012 and during the writing of One for the Boys she continues to remain connected with her newly found family the Rangers and their families. Throughout her lifetime, Cathy has dabbled at writing; poetry, songs and short stories.

Will she write another book? Absolutely, perhaps two!

One for the Boys is available at Amazon and locally, in St. John’s at Chapters and Coles Stores, and Indigo online.

All images submitted by author

Leave A Reply